by: Chelsea Dickson Oct 6, 2014

by: Chelsea Dickson Oct 6, 2014

Courtesy of: The Tartan

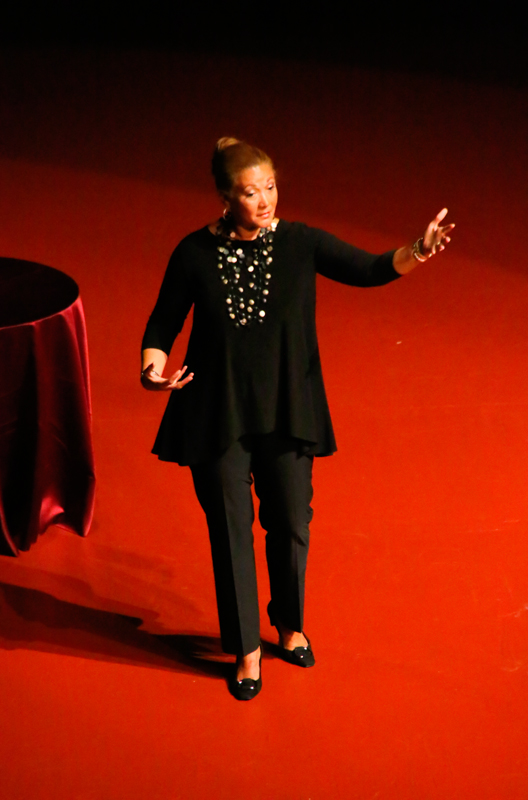

“America’s conversation on race has only just begun,” said NPR correspondent Michele Norris during a talk on racial diversity last Wednesday at the Carnegie Music Hall. The lecture, titled “Eavesdropping on America’s Conversation On Race,” proved more than an exercise in listening, and rather an invitation to an open dialogue on race in America. Hosted by the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, the event was held in tandem with the museum’s new exhibit “Race: Are We So Different?”

Michele Norris began hosting NPR’s All Things Considered after working for news outlets such as The Washington Post, the Chicago Tribune, and the Los Angeles Times, eventually winning both an Emmy and Peabody Award for her coverage of the Sept. 11 terror attacks in conjunction with ABC News.

In 2006, Norris was inspired by the term “post-racial” to explore the real conversations Americans were having about race. Today, Norris directs her social experiment, “The Race Card Project.”

People from America and elsewhere may send in their six-word stories about their experiences with race to the “Project.” More often than not, Norris finds people are eager to share many of their anecdotes.

At her lecture on Wednesday, Norris shared some of the accounts she’s heard while directing “The Race Card Project.”

Once, a woman revealed she had saved an invitation to a lynching that was sent to her father. In a more intimate moment, Norris recalled learning that her own father had been shot in Birmingham, Alabama after serving in WWII. While still in uniform, her father attempted to enter a center where he was taking a class on the Constitution but was stopped by a police officer. A scuffle ensued, and the officer attempted to shoot her father. Luckily, he escaped with only a flesh wound.

Norris’ father, however, never told her about this experience. Instead, she said, he decided “to pass on ambition” to his children rather than a history of violence and oppression.

For Norris, these small moments of racial tension add up to create a person’s “wealth.” Norris proposed a new definition of wealth in relation to race. America’s “wealth” of diversity comes from these small ways we experience race, Norris said.

She said that although sometimes people’s words might sound harsh or off-putting, their curiosity to talk about race and diversity should be encouraged. Norris ended the lecture by reading some of the six-word “Race Card” stories she found funny or thought-provoking: “It’s a non-issue when aliens arrive,” “What ever happened to midnight basketball?,” “I am Asian, not a genius,” “Ghetto’s a place, not an adjective”, “Hated for being a white cop,” “Delicious ambiguity: the permanent in-betweener,” and “Still more work to be done” to name a few.

Norris’ own six-word story? “Fooled them all, not done yet.”

Many Carnegie Mellon community members who attended the lecture hope that projects like “The Race Card Project” inspire more campus dialogue on race.

For Assistant Director in the Office of the Dean of Student Affairs Shernell Smith, conversations about diversity strengthen the Carnegie Mellon community: “Food, festivals, and fairs only get you so far,” Smith said. “With the unanswered questions in the room — or the elephant in the room — these kinds of dialogues allow for us to dig a little bit deeper and really have those meaningful exchanges with one another. Because those meaningful relationships are about collaboration…. As President Subresh said earlier this week, ‘Diversity inspires innovation.’ And Carnegie Mellon is filled with innovation.”

“She really included a lot of multicultural issues; she hit on Asian ethnicities, Hispanic ethnicities, blacks, whites. I even like how she mentioned how whites are sometimes underprivileged because of the inability to say certain things that colored people can,” sophomore English major Melanie Diaz said.

For others, the lecture sparked some more critical thoughts on Carnegie Mellon’s relationship with race.

“CMU has a huge problem in that we not only devalue the humanities, but we pretend that science and technology are these holy grails of objectivity, when science and technology, in both education and application, both have a huge history of racism and sexism,” junior chemistry and creative writing double major Sophie Zucker said. “How can we call science and technology today not racist and sexist when 60 years ago we were saying that racial differences indicated intelligence?”

Others found the lecture’s tone fresh and hopeful.

“It wasn’t just ‘let’s acknowledge that race issues are alive,’ ” said the secretary of the Black Graduate Students Organization and mechanical engineering doctoral candidate Nateé Johnson. “It was also ‘Hey, let’s be comfortable in our own skin while recognizing that it’s not that different from someone else’s.’ We are naturally curious beings. We’re evolved to notice differences.… We don’t have to let stereotypes dictate how we treat people, or how we perceive people are treating us. This race conversation doesn’t have to be abrasive.”