Elise DuBord,

Cedar Falls, IA.

Growing up in the Midwest, I started studying Spanish as a second language in high school, fascinated with learning about other cultures and enchanted with the idea of traveling to or even living in a new country. As a middle-class white kid, I was completely unaware of the privilege I brought to learning Spanish. I was not studying Spanish because I had to; I was doing it because I wanted to. It was interesting and exotic, and there was no penalty to me if I didn’t do it well or spoke Spanish with an accent.

After living abroad for a few years in college, I was able to call myself a Spanish speaker, and as a young adult, I wore that label proudly and somewhat cockily, showing off my Spanish abilities any chance I got. One day at work, I greeted a Latina client who was about my age in Spanish. She sneered at me and forcefully (and fluently) said, “I speak English.” I was mortified. Had I offended her? Was it wrong for me to greet her in Spanish? Did I have a right to make a claim on being a Spanish speaker?

In retrospect, I realized that there are no easy answers to these questions and I had much learning to do. Becoming a fluent Spanish speaker did not give me an open invitation to speak Spanish with anyone, anywhere. With many missteps along the way, I have become more sensitive to the language needs and desires of the people I encounter. I have learned to acknowledge and accept that sometimes I am not invited to speak Spanish, and it is not my place to control that conversation.

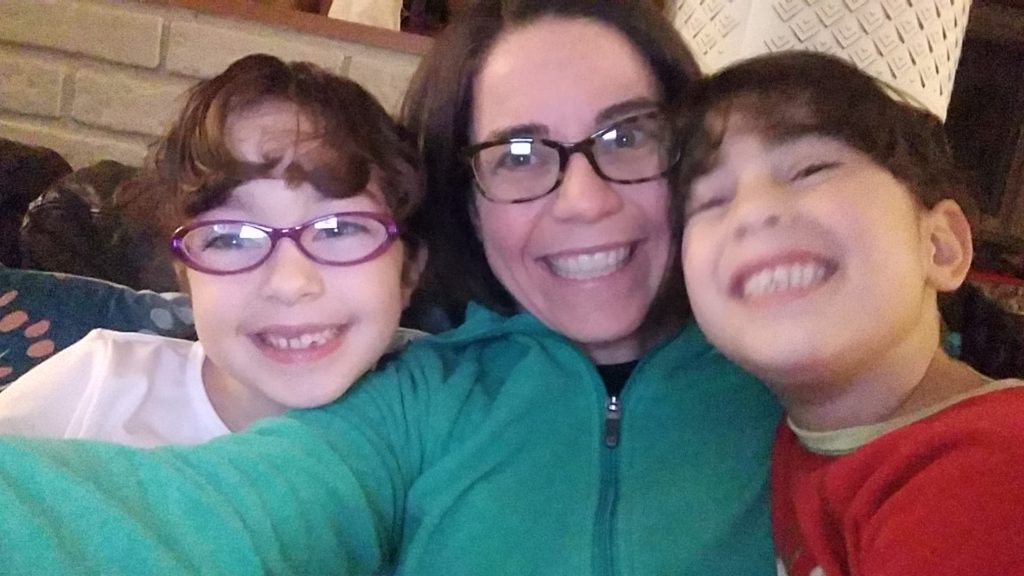

Fast-forward to a decade later to when my kids were babies and my husband (a native Spanish speaker) and I had decided to maintain Spanish as the language of our family. I knew that I would speak to my kids in Spanish from the start; we wanted them to be able to communicate with their extended family in Puerto Rico and grow up bilingually. In all of the first exciting moments of becoming a parent and meeting your kid for the first time—a new human being who you love and talk to—I was doing it in Spanish. A mother passing on someone else’s mother tongue.

At first, it felt awkward; I realized that I didn’t know how to talk to babies in Spanish. I felt self-conscious on the playground talking to my baby girl in Spanish while pushing her on the swing. Were other people listening? Did they think I was a fake? Most of the time I have felt lucky to be part of helping my kids grow up bilingually. Other times it has felt like a lot of work.

Now my kids are in grade school and are bilingual, even as ever-powerful English persistently erodes away at the edges of their Spanish. As far as I know, they haven’t experienced discrimination for speaking Spanish. But I also recognized that they are speaking Spanish from a place of privilege too. Their fair skin, middle-class upbringing, U.S. citizenship, and perfect English has so far allowed them to speak Spanish without many consequences.

I have many hopes for my kids. I hope they don’t face discrimination because they are Latinas and Spanish speakers. I hope that they are curious, empathetic, and kind. I hope that they proudly maintain their Spanish.